Readers last week will know that I was giving a talk last Friday at a conference in Northumberland. Given that I like to share my work I thought I’d put it up for you this week – I’ve even included some of the slides. Lucky you! So, without further a do, I present to you – a paper.

I want to start with a story.

A long time ago, in a town not so far, far away (Gateshead to be precise) a terrifying structure was placed on a hill. This structure was the cause of great fear and anger amongst the surrounding residents. Its presence loomed over the nearby villages and became renowned across the country.

Some debated whether it was a “heavenly body or an angel of hell” whilst others attacked the powers that had forced it on their land, claiming “‘if anybody other than this authority had been involved it would have been thrown out.’” As one local newspaper of the time put it, ““Hostility never sounded louder.”

This structure?

The Angel of the North…

Joking aside, I want to suggest that the Angel of the North is a useful visual reminder of a more barbaric structure that featured prominently on the North East Landscape – across the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. For the purposes of this paper, the North East here refers to Durham, Newcastle, Berwick and Morpeth. These are a selection of sites of execution from the Northern Assize circuit.

This paper will argue that it is the gibbet far more than the gallows and the immediate symbols of execution that have had a lasting effect on the criminal topography of the region. In large part owing to their relative permanency, making them sites whose meaning changed over time. In this paper I want to look at the three instances of its use in the North East and illustrate how far the gibbet often strayed from its original intention as a visual symbol of the grisly ends of crime and how it is still a contentious structure to this day.

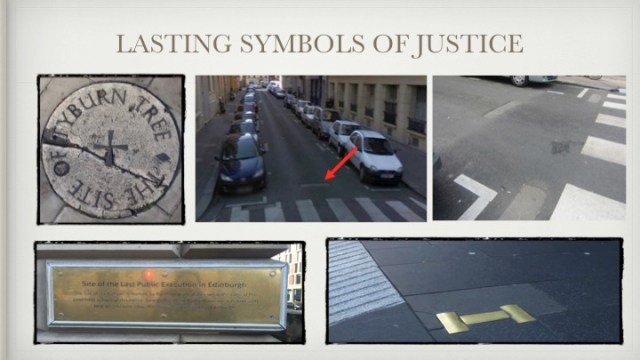

I have just returned from a British Crime Historians conference in Edinburgh and whilst I was up there I took some time out to look at a few Scottish sites of execution. As is often the case, these are quite clearly marked. Here are a few examples from Edinburgh and further afield. I have even included a French one for Dominique (Guest Visiting Professor Dominique Kalifa)

(I am reliably informed that these stones highlighted by my red arrows mark the five slabs that held together the foundation of the Paris guillotine, built at the entrance to the now closed and destroyed Prison de la Roquette).

The North East is notable for an absence of these memorials. Indeed, one has to look very closely to find any semblance or visual record of capital punishment in the region.

For example these plugs (above) are the stone fillers for the holes that used to hold the supporting bars of the gallows. After 1816, executions in Durham moved from Dryburn to outside the court-house. The prisoner would walk out of the window pictured, directly on to the gallows platform just below. But these plugs are hardly an explicit reminder – great pub quiz knowledge at best.

In comparison the gibbet had a much more lasting effect on the North East landscape and in one particular case still does.

First though, a quick bit of context.

By the mid-eighteenth century, there was a common perception that crime was on the rise in England and Wales, fuelled in part by the recent demobilisation of troops from the war.

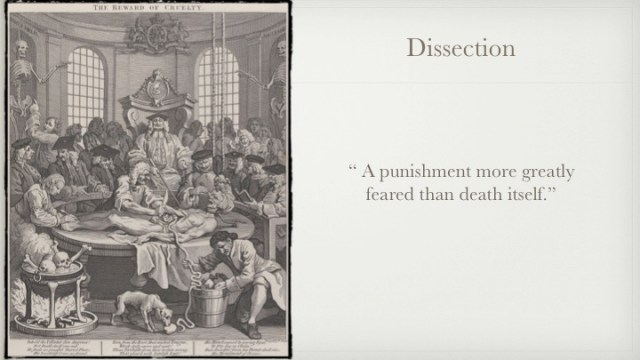

The perception was that hanging wasn’t punishment enough for some crimes and that the whole apparatus of state punishment lacked the necessary clout and terror. Several bills were passed in response to this fear, chief amongst them the Murder Act of 1752. The Act for “Better preventing the horrid crime of murder” dictated that, in addition to execution, “some further terror and peculiar mark of infamy be added to the punishment.” In its central aims the Act was in line with others in the period that Historian James Beattie has said sought to

“reassert the centrality of hanging and of deterrence by terror at the heart of the English penal system.”[2]

The “further terror and peculiar mark of infamy” dictated by the act were two fold. The criminal after death would either be subject to public dissection by the Barber Surgeons. A punishment, as one historian has suggested, “more greatly feared than death itself.”

or gibbeting (otherwise known as hung in chains).

A sentence of which the Monthly Chronicle of North-Country Lore and Legend stated,

“Edgar Allan Poe and the Spanish Inquisition could scarcely have been more fertile in devising means of human torture.”

It is the latter on which I will focus today.

If a criminal were sentenced to be gibbeted, his body would be taken from the gallows and transported to, or nearby, the scene of his crime, his body placed in an iron cage and then hung from a 20-30foot high wooden post.

In reality, the gibbet was very sparingly used across England and Wales. Recent findings from the excellent Wellcome Trust funded project the Harnessing of the Power of the Criminal Corpse have shown the following.

Of the 1,394 Offenders that were capitally convicted between 1752-1832 in England and Wales only 134 were hung in chains – roughly 9.6%. In comparison over 80% were dissected. The North East was no exception; in the same period only 3 people (roughly 9%) suffered the gibbet. One of the great ironies of the Murder Act is that the punishments it crystallised, had long been in operation before. Indeed, recent studies have shown that the use of the gibbet peaked in the 1740’s. Any lovers of the North east coastline, may well be aware of Curry’s Point, a headland to the North of Whitley Bay – so named after the gibbeting of Michael Curry for the murder of landlord Robert Shervill in 1739.

Unlike dissection, gibbeting was an exclusively male punishment. Also, unlike dissection, the gibbet was not exclusively used for murderers. Indeed, in the North East the first instance of its use was for Robbing the Mail. A case which I will now turn to.

Travelling from Newcastle to London in 1772, the Reverend James Murray was met by what he called a “grave and solemn” scene on Gateshead Fell (Modern day High Fell). What he saw inspired the following lament.

Poor Hasslet! hadst thou robbed the nation of millions, instead of robbing the mail, and pilfering a few shillings from a testy old maid; thou hadst not been hanging a spectacle to passengers, and a prey to crows…Were all the robbers of the nation hanging in the same situation, there would be some appearance of justice and impartiality. But the poor only, can commit crimes worthy of death,—and those also must be enemies to the c—–t, or lukewarm in its interests”

Murray had seen the body of the Highwayman Robert Haslett. Executed at Durham in 1770, for robbing the mail on the notoriously treacherous Gateshead Fell. Eighteen years after its inception, Haslett had been the first person in the North East to suffer the gibbet under the terms of the Murder Act. By Murray’s account, his body still hung in the cage two years after first being hung. This was not uncommon, indeed the Newcastle Advertiser reported the following instance in 1812.

“Extraordinary circumstance – About seven years ago a man was gibbeted on Saxelby Moor for the murder of his wife. In his mouth has recently been found a bird’s nest with young and what is more remarkable, the same species of bird (a willow biter) built her nest there last season.”

Another account in 1776 appears to show that Haslett’s body is still encaged and indeed the observer, one Jabez Maud Fisher an American Quaker, believed “he could not have long been dead” as the “flesh seemed perfect.”

We do not know exactly when Haslett’s body and gibbet were taken down but he reappears in a surviving ballad from 1805, in which the standing Army of Gateshead warn Napoleon what he’ll face if he lands on their turf. Apologies for the accent and given the origins of our esteemed visiting Professor, I would like to suggest that Gateshead-Franco relations are far better these days and he should not expect the same welcome.

Whether Napoleon caught wind of the Gatesiders’ threat to gibbet him on Gateshead Fell isn’t clear, but needless to say he never got round to visiting. Also if anyone knows what “Taings Weel” or “Whaings weel” mean please catch me afterwards.

The pond in question was the body of water at the side of which Haslett’s gibbet sat, indeed in his earlier account of passing the site in 1772 the Reverend James Murray noted it was

At the foot of a wild romantic mountain near the side of a small lake…his shadow appears in the water, and suggests the idea of two malefactors…This dreary place is well calculated for raising gloomy ideas, which tend to craze the imagination.[7]

Further personal research has shown that eventually the pond in question was filled in. The land was purchased by one Michael Hall, following the Enclosure Act of 1809. Michael Hall would later become one of Gateshead’s first mayors. Even in spite of Michael Hall’s filling in of the pond which later became a “a beautiful piece of green sward”[8] we see it still noted as a topographic feature under a derivation of Haslett’s name in a report to the Natural History Society of Northumberland on a recent pit disaster. Describing the Fell, the author Mr Buddle notes

“From the quarry, near the Seven Stars, on Gateshead Fell, it runs to the 10-fathom upcast Dyke under Heslop’s Pond, where it is thrown out for about 50 yards.

Similarly, Heslop’s Pond, appears on an 1877 Ordnance Survey Map.

A century after his gibbet had been removed this terrifying symbol of the ends of crime had transmogrified and become the site of multiple conflicting meanings. At once the site for a great ghost walk, a warning to invading armies and a noted landmark.

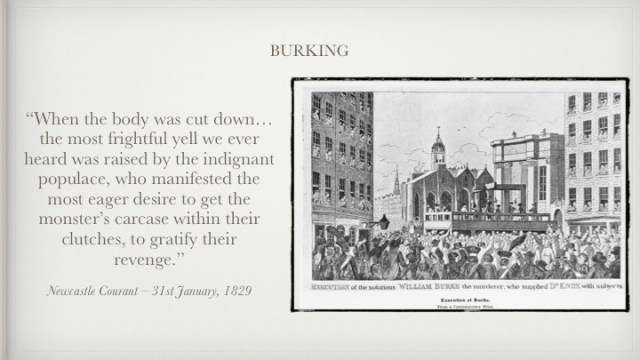

Some fifty years after Hazlett’s gibbet was first erected, the final gibbet ever to be placed in the North East was being set in place in Jarrow. That same year the post-mortem punishment of dissection for murder had been removed by the Anatomy Act. The punishment of Hanging in Chains however, remained on the statute, although it had long since fallen into disuse – a presumed barbaric relic. As I discovered in my travels in Scotland, even William Burke of Burke and Hare fame, was not deemed worthy of the gibbet in 1829. The Judge arguing that the sight of such a thing would offend the public eye.[9] Reports of the crowd at Burke’s execution would seem to suggest they disagreed. Indeed, the Newcastle Courant noted

A further note in the paper gave an indication of what the crowds revenge might have been.

As one among many proofs of the feeling of the public…we may notice the fact, that in anxious expectation of the gibbet being erected, a crowd of people assembled yesterday at the head of the Wynd…and remained there the whole day[11]

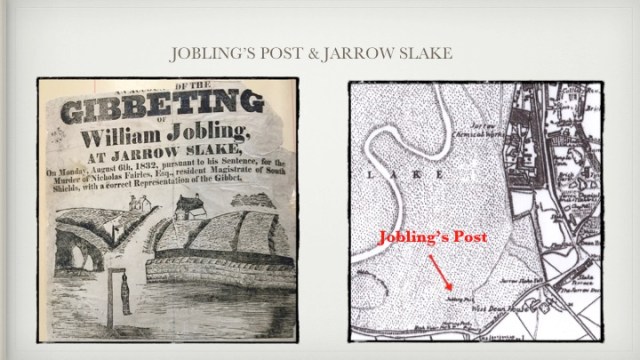

Given the judicial reluctance to use the sentence anymore it was a great shock when one Jarrow Miner was sentenced to execution and gibbeting in 1832. Indeed, so rare was the sentence that several local newspapers wrongly reported at the time that the punishment had been brought back specifically for the case.

William Jobling and Ralph Armstrong were charged with the murder of 72 year-old Justice of the Peace, Nicholas Fairlees. Fairlees was beaten by the roadside in Jarrow and left for dead, he died of his injuries ten days later. Jobling was apprehended, but Armstrong escaped. Their crime was a brutal episode in an increasingly bitter dispute between the recently formed miners unions and mine owners that had seen strike action across the region. The perceived harshness in the local community of Jobling’s sentence was further exacerbated when, in the weeks between his charge and execution, another Miner – one Cuthbert Skipsey – was shot dead by a Policeman whilst attempting to mediate in an argument between colliery workers and the police. The policeman’s sentence, just six months hard labour.

*For anyone aware of the famous pit poet Joseph Skipsey, Cuthbert was his father (Joseph was born months before his father was shot).

Jobling’s gibbet was erected in a body of water called Jarrow Slake and put under armed guard for two whole weeks, such was the fear that it would be stolen away.

Attempts to remove the gibbet were not unheard of, even in the case of Michael Curry in 1739, of Curry’s Point infamy, the Newcastle Courant printed a warning that any attempts to steal the body or gibbet would result in a sentence of seven years transportation – a similar warning appeared in both local and national paper for William Joblings gibbet.

In spite of the efforts of the authorities on the night of 31st August 1832, it was surreptitiously stolen. The post itself stayed in place until 1856, when it was removed by workmen building the new Tyne Dock, but Jobling’s body and the gibbet cage were never recovered.

However, the story doesn’t end there. Jobling has become the stuff of folkloric history.

Just in the last decade alone he has had ales named after him, operas performed in his name at the Royal Opera House in London and after long petitioning a plaque has been erected in memory of him. A replica of his gibbet stands to this day in South Shields Museum. It could perhaps be argued that Jobling was a classic case of the punishment making a martyr of a malefactor. Had Jobling simply fallen victim to the hangman’s noose or surgeons knife, his name may well have been long forgotten. His post-mortem punishment gave him his infamy. For proof of such, one need only look at the fate of Cuthbert Skipsey. No ale or opera for him. Indeed, the multiple afterlives of Jobling and his recent re-evaluation as a scapegoat of a sanguinary state system – are as much a product of his punishment as they are a reaction to it.

As one broadside of the time stated. Jobling’s gibbet was“A Warning for the Future and a Memento of the Past.” Standing empty its warning must surely have been that this punishment no longer worked. As if further proof were needed, just weeks after Jobling was executed, the final case of gibbeting in England and Wales took place in Leicester. The gibbet was erected for Murderer James Cook, but following petitions to the Home Office about how many people it was attracting, it was removed within weeks.

Now, For anyone au fait with the North East landscape, they will know that I have skipped a case. In fact, I have saved the longest standing gibbet till last as proof of the gibbets power to still divide.

In 1792, William Winter was sentenced to death alongside Eleanor and Jane Clarke for the murder of Margaret Crozier, at her shop in Elsdon, near Rothbury. Part of the renowned Winter’s Gang, William was originally sentenced to dissection alongside his accomplices but this was later changed to Hanging in Chains near the scene of the crime.

For anyone who knows that particular part of the North East. They will know that Winter’s Gibbet still stands to this day.

Local Historian Eneas McKensie noted in 1822 that

This loathsome spectacle (i.e. Winter’s Gibbet) at length fell into pieces and another gibbet, on which the rude figure of a man is suspended, occupies its place.[12]

This was the first of many renewals, restorations and rebuilds of this brutal structure. Indeed Winter’s gibbet has been continually restored over the centuries and at various points in time, an effigy of some sorts has been hanging from it. When I visited the gibbet last year it stood devoid of any prey. However, even to this day it is a subject of much local contention and controversy.

In 2011 Air Farmers Ltd submitted plans for wind turbines to be built beside Winter’s Gibbet. The plans caused uproar and led to the formation of the Middle Hill Action Group. Tempers reached a pitch when one of the developers referred to the Winter’s Gibbet as ‘nothing more than a Victorian Disneyland’ leaving Councillor Steven Bridgett apoplectic:

Over two hundred years after this “loathsome spectacle” had been placed on the land, the Parish Council are fighting to keep it as a popular landmark and treasured relic. Indeed, Elsdon Parish Council even offered to raise funds to put a replacement head on the gibbet as “many visitors…asked for directions to the site and wanted to see the gibbet in a complete state with the “head.”

To the councils dismay it still stands empty. As to its potential future one could do worse than to ask a Nobel recent Nobel prize winner.

The answer my friend is blowing in the wind.

DISTRACTION 1: Bob Dylan

I can’t end on Bob Dylan without saying anything further. I grew up in a house where Dylan was obsessively played and his music is engrained in my soul. He is a belligerent bastard though, but I think that’s what makes him such an enigma. The whole saga surrounding the Nobel Prize made me seriously question the intelligence of this ‘expert panel’ who appeared shocked that a man renowned for not doing what is expected of him, didn’t do what was expected of him. Anyway, onto the music – there are too many great songs, but one of my personal favourites is Song to Woody. Enjoy.

DISTRACTION 2: Grief is the Thing With Feathers

One of the downsides of a PhD is you lose your love of reading for readings sake. After having your head in books all day I like to watch something mindless on the TV now, where I once would have read (the Apprentice if you’re asking). Having said that, my girlfriend’s parents live in Corbridge and have a fantastic local bookshop (Forum Books). I was in their last week and picked up Grief is the thing with feathers and it turned out to be a brilliant choice. It’s unlike anything i’ve ever read before, but it is a remarkable book. I read it all in one sitting and found it a deeply moving work.

DISTRACTION 3: execution – monty python

3 Distractions! after a 3,000 word blog! – surely no one made it this far! Well, if you did thank you. Your reward is a sketch that I was desperate to put in my talk, but just couldn’t quite crowbar it in. Academics aren’t the funniest bunch to be fair! I am always struck by the confusion surrounding who is responsible for c18th and c19th post-mortem punishments and am often convinced that some people must have slipped through the cracks. If they did, I hope it was like this.

Pingback: Gibbets and Gin – lastdyingwords