Anyway, I hope you all got what you wanted or, better still, made sure that people without got what they needed. On that note, after having plugged BBC One’s A Christmas Carol in my previous blog, I watched the final episode and was struck by the following passage. Scrooge is approached by a man in the street raising money for the poor,

Although Scrooge’s suggestion of prison as an alternative to charity is worthy of a blog in itself, it is the treadmill that is of particular interest here – not least because of the frightening amount of weight I have put on from Christmas excess.“At this festive season of the year, Mr. Scrooge,” said one of the gentlemen, taking up a pen, “it is more than usually desirable that we should make some slight provision for the Poor and destitute, who suffer greatly at the present time. Many thousands are in want of common necessaries; hundreds of thousands are in want of common comforts, sir.”

“Are there no prisons?” asked Scrooge.

“Plenty of prisons,” said the gentleman, laying down the pen again.

“And the Union workhouses?” demanded Scrooge. “Are they still in operation?”

“They are. Still,” returned the gentleman, “I wish I could say they were not.”

“The Treadmill and the Poor Law are in full vigour, then?” said Scrooge.

“Both very busy, sir.”

“Oh! I was afraid, from what you said at first, that something had occurred to stop them in their useful course,” said Scrooge. “I’m very glad to hear it.”

Created in 1818, the treadmill was the invention of Norfolk born engineer, William Cubitt and was used as a punishment in the English penal system for most of the nineteenth century until it was abolished from the penal arsenal by the Prisons Act 1898.[1] Writing in the late nineteenth century one Newcastle paper recorded that the invention was the result of a chance encounter between William Cubitt and a Magistrate, who bemoaned the lack of discipline for prisoners. The magistrate implored Cubitt, “I would to heaven you could suggest some mode of employing these fellows. Could anything like a whel (sic) become available?'[2]

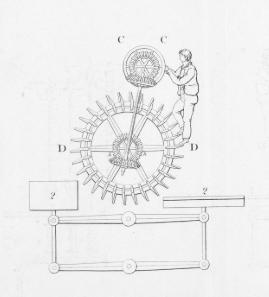

The treadmill took many different forms, but most shared common characteristics, namely a series of steps around a hollow cylindrical barrel. Prisoners would take their place on the steps and as the device commenced rotating, it forced prisoners to continue stepping along a series of planks/steps. Owing to this it was sometimes colloquially referred to as the ‘everlasting staircase’. In some instances the power that was generated by the effort of the prisoners was used to either pump water or grind corn, but frequently it didn’t serve any purpose and was purely a punishment for punishment’s sake. Previous scholars have noted the change in its purpose over time arguing that what ‘had begun the century as a gruelling physical experience became one that tortured the prisoner, body and soul, leaving many destroyed by the experience.’[3]

An illustration of a treadmill at Brixton Prison. (Saxthorpe, near Aylsham, Norfolk; 1824). Shelfmark 6307.n.37. Image courtesy of British Library. ‘This particular treadmill could accommodate up to twenty-four prisoners at one time, with each man moving along the apparatus from left to right until a new prisoner joined at the far end and allowed them a rest period. In a twenty-four man mill, the rest period amounted to twelve minutes every hour.’ https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/description-of-the-tread-mill

One of the most famous recipients of the punishment was Oscar Wilde, during his time at Pentonville prison. Richard Ellman, his biographer, recorded that he spent up to six hours a day on the treadmill and indeed notes from the prison chaplain recorded how the toll of labour had pretty swiftly left Wilde ‘crushed and broken’.[4] In his poem The Ballad of Reading Gaol, Wilde opined the monotony and hardship of these sort of thankless and incessant punishments (amongst them crank turning and picking oakum – separating strands of rope).

With midnight always in one’s heart,And twilight in one’s cell,We turn the crank, or tear the rope,Each in his separate Hell,Oscar Wilde – The Ballad of Reading Gaol https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45495/the-ballad-of-reading-gaol

These were the sort of punishments that Foucault referred to when he talked of a fundamental change in the nineteenth century from expressly physical and public punishments to a system of private punishment that ‘no longer touched the body. If it did, it was only to get at something beyond the body: the soul.’ In many ways the nineteenth-century penal system was something of a Sisyphean system.

This Christmas has been a joy and I have read more books in a week than I had in the last 6 months. I started with Dickens’ A Christmas Carol as I wanted to see just how much artistic licence the BBC adaptation had taken….turns out a lot (but I still enjoyed it). However, my favourite read was Oliver Sack’s Everything in its Place: First Loves and Last Tales – a collection of his short essays (is there anything better than a beautifully written collection of short essays). Sacks was a neurologist, regarded by some as the ‘poet laureate of medicine’. He has a wonderfully engaging and adept style that entices the reader. Particular highlights include his early disastrous forays into cephalopod collecting and his insights into the healing properties of gardens – ‘I have found only two types of non-pharmaceutical “therapy” to be vitally important for patients with chronic neurological diseases: music and gardens.’

I want to see you not through the Machine. I want to speak to you not through the wearisome Machine.

E.M. Forster – The Machine Stops

This reflection put me in mind of a great music video I saw (i should add I am not a fan of the track though – still works on mute).

So, how about for 2020 rather than making unachievable resolutions about the gym we all go for something achievable and mutually beneficial – we all use our phones for fifteen minutes less a day. Just embrace the moments of silence free from the siren call of social media likes or better still read. Or even just look up and smile at the world around you (not for too long though otherwise you’ll be incarcerated and put on the treadmill). Have a great new year and for anyone in a particularly catastrophic mood, I will leave you with the final words of Sacks’ essay.

As I face my own impending departure from the world, I have to believe in this – that mankind and our planet will survive, that life will continue, and that this will not be our final hour.

Oliver Sacks – Everything in its Place p. 258 (full article available here).